The Anglo-Russian Antagonism Part 2 : The 19th Century ‘Great Game’

Posted by Terry Boardman on Nov 21, 2022 in east west issues, nwo | 0 commentsThe two largest empires, the two greatest imperial rivals in the world for most of the 19th century were the British and the Russian. In the middle of that century their rivalry led to a major military conflict between them in Russia’s Crimea, a region thousands of miles from Britain and France, which those two allies invaded in 1854. Since the Crimean War, the Anglo-Russian antagonism has continued, on and off, until today in other forms than direct military conflict between the two countries. What is really behind it? Where are its roots to be found? In the 19th century the roots were essentially twofold: first, British Russophobia that focused entirely on British possession of India and the British elite’s fear of losing India to Russia; and second, the disdain, contempt and outrage that British Whigs and Liberals in particular felt for what they saw as Russia’s political and cultural backwardness and its autocratic system. These two factors remain operative in Britain today, but in the 20th century they were joined by an important third factor, which will be discussed in the third and final article in this series.

From Peter to Paul and Alexander

By the end of the 18th century, the two states that were England and Muscovy in 1600 had become the world-spanning imperial powers Great Britain and Imperial Russia – the ‘Whale’ (as Britain was referred to due to its sea power) and the ‘Bear’. From its island point, Britain had expanded over the oceans to almost the entire global periphery, while Russia had simply expanded overland: west to the Baltic, south to the Black Sea and massively east to Siberia and the Pacific Ocean. In the 18th century the British elite were preoccupied with dealing with France and replacing it as the global Power. The Russian Czars after Peter the Great (1682-1725) continued with a gradual westernisation of their country and sought to expand against Muslim powers in the south and southeast, the Ottoman Turks and the Persians. Relations between Britain and Russia had been good on the whole, except during the Seven Years War in mid-century when they were allied to Powers on opposite sides, but their own forces never actually clashed. Real tension only began in the time of Catherine II (the Great) in the 1790s, when William Pitt the Younger was Prime Minister in Britain. The British elite, always concerned about their hold on India, so important to the British economy, began to feel that Russia might pose an indirect or direct threat to British control of India because of Empress Catherine’s aggressive policy towards Turkey, which the British saw as a gatekeeper state that served their interests in keeping other European Powers away from British India. When Russia took the fortress of Ochakov (near Odessa) after the Treaty of Jassy (1792), William Pitt aggressively threatened war and equipped a fleet to sail to the region, but the very capable Russian ambassador in London organised a campaign that weakened Pitt’s position on the issue of Anglo-Russian relations and Pitt backed down.

Another problem emerged when the eccentric son of Catherine the Great, Czar Paul I (1796-1801), succeeded her and having first been anti-French – the revolutionary French had publicly executed their king and queen, which the traditionalist Paul did not appreciate – he shifted to a pro-French, anti-British policy because he felt the British had put undue pressure on his Scandinavian friends in Denmark and Sweden and because in October 1800, the British Admiral Nelson had taken the island of Malta, traditionally ruled by the Knights Hospitaller, a Roman Catholic Order of which Paul, who was very concerned about chivalric matters, had only recently become the Grand Master, despite his being Russian Orthodox. As Malta was a strategic naval asset in the middle of the Mediterranean, the British did not give the island back. Paul was furious and sought to hit Britain at its weak points – its commerce and its colonies. He allied himself with Napoleon and intended to stop British trade in the Baltic, a vital region for materials essential for the Royal Navy, and combine with the French in a great march to India, a project his new French ally Napoleon had already tried to realise in 1798 with his failed expedition to Egypt. Napoleon knew that India was the key to Britain’s grip on world trade. The British response to Paul’s move was not long in coming; on 23 March 1801, when 20,000 Russian Cossacks were already on their way to India and had reached the Aral Sea, Paul was assassinated by a conspiracy of aristocrats led by Counts Pahlen and Panin, the Hanoverian General Benningsen and the Georgian General Yashvil, together with the three brothers Zhubov, whose sister was the lover of the skilful British ambassador, Charles Whitworth, who provided funding for the plot. The conspirators even managed to get Paul’s son, Czarevitch Alexander, to keep silent about it; he went along, wrongly assuming his eccentric father would not actually be killed. Those men had their own, mostly venal, personal reasons for opposing Czar Paul, but Paul’s dramatic demise was certainly in the interests of British foreign policy. Ambassador Whitworth’s Russian lover Olga Zherebtsova, in whose house the conspirators had made their plans, soon followed Whitworth to Britain, but there he dumped her and married the wealthy widow of the Duke of Dorset who was worth £13,000 a year and owned the borough of East Grinstead. Needless to say, the new Czar Alexander (1801-1825) immediately recalled his father’s military expedition to British India and returned Russia to an anti-French policy. He did not execute any of the conspirators involved in his father’s assassination.

It was during the reign of the new Czar Alexander I that relations between Britain and Russia headed into the poisonous direction which they have maintained ever since, except for two very brief interludes around World War I (1907-1917) and during World War II (1941-45). The period after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 was when, after a thousand years of gradually approaching one another, the two countries that had now become the Great Whale and the Great Bear entered into a seemingly permanent state of hostility. And it began, at first, because of the British elite’s paranoia about the possible loss of India, a paranoia which later in the 19th century was disguised under the very British term: “The Great Game”.

Russophobia after 1815: The Great Game

It was a dispute over Poland which had prompted the first serious wave of British Russophobia after the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Lord Castlereagh, the powerful British Foreign Secretary at the time, had strongly opposed Czar Alexander I’s wish to be crowned king of Poland. The anti-Russian, Polish forgery known as the Testament of Peter the Great, first circulated by Napoleon in 1812, accused the Russians of having designs on British India amongst other things. It was first translated into English at this time. Guy Mettan in Creating Russophobia (2017) writes: “The imperialist lobby, increasingly powerful in London, would never thereafter lose sight of Russia and became the most determined adversary of the Russian cause….” By the 1820s, letters, articles and polemics began to appear frequently in the British press about the Russians’ thirst for unlimited expansion and the threats they posed to British interests. The Whigs, who represented the tenets of British free trade and the middle-class liberal opposition to the Tory government, were also vehement in their criticism of Russia, which they regarded as backward, even barbaric and illiberal. Being often anti-monarchical themselves, they naturally opposed Czarist autocracy. This vehemence passed on to the Liberals in mid-century and is still the case today with such media as The Guardian newspaper and the BBC. The forged Testament of Peter the Great was repeatedly alluded to, often without being mentioned explicitly, in absurd charges that the Russians were planning “to take over the world”. Although the British government found itself allied with the Russians over the question of Greek independence from Turkey in the 1820s, the British Press kept up the drumbeat of Russophobia, always suspecting that Russia was intending to take Constantinople and penetrate the Mediterranean, thus posing a potential threat to sea and land routes to India. Then again came the Polish issue, when the Poles rose in revolt against the Czar Nicholas I in 1830, causing great emotion among the English middle classes when the revolt was crushed. Needless to say, then as now, the British middle classes knew hardly anything about actual life in Russia or Poland except what their Press told them. A well-known cartoon by the cartoonist Granville went the rounds featuring a Cossack smoking his pipe, standing amidst Polish corpses. As usual, memories were short: dragoons had massacred civil rights protesters in Manchester only 12 years before. In 1833, Russia and Turkey signed a peace deal but this only enraged the British Press, fearful as ever that Turkey might allow the Russian navy into the Mediterranean. In fact, the Russians were just as worried about the consequences of Turkish decline as were the British. The peace deal with Turkey allowed Russia fully to establish control over the region of Circassia in the Northeast Black Sea region, but the Circassians objected. The British secretly sent weapons to the Circassians but were found out, and the two countries came close to war, but the British backed down, as they could secure no continental allies for a fight with Russia at that time.

The term ‘Great Game’ was coined by a British officer, Arthur Conolly, who tried to get Turkmen tribes to revolt against Russia but ended up beheaded in Bokhara in 1842. Throughout these decades there were numerous intrepid ‘adventures’ by British soldiers, agents and spies in the depths of Central Asia; their exploits, eagerly reported in the Press, fuelled the fires of Russophobia in Britain.

One of these ‘adventurers’ was the enigmatic English discoverer, translator, writer, orientalist, secret agent, diplomat and occultist Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890), widely-travelled and skilled in 29 Eurasian languages. He was a member, together with the novelist and politician Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Lord Stanhope, of the occult group Orphic Circle and regularly accessed ‘the other world’ through his wife Isabel, a medium. Burton said: “I believe the Slav to be the future race of Europe, even as I hold the Chinese to be the future race of the East. In writing politics and history which may live after one is long forgotten, one must speak the truth, and bury repulsions and attractions.”(1) He repeated this at a dinner in the presence of Lord Palmerston and added that Russia and China would one day fight over Central Asia.”

British paranoia about India and suspicions that the Russians were using the Persians to attack India resulted in the First Afghan War in 1839, which ended so disastrously for the British; they invaded the country but were slaughtered and after eventually recapturing Kabul, they withdrew and peace was restored with difficulty in 1842. The Afghan ruler Dost Mohammed said: “I have been struck by the magnitude of your resources, your ships, your arsenals, but what I cannot understand is why the rulers of so vast and flourishing an empire should have gone across the Indus to deprive me of my poor and barren country.” He was clearly not au fait with the imperatives of ‘the Great Game’…

The Egyptian crisis in the early 1840s further stoked British Russophobia. Mettan notes: “In just 25 years, English public opinion had been completely turned around. From privileged ally, which had entered into war against Napoleon alongside Great Britain out of unwillingness to participate in the anti-English blockade wanted by the French emperor, Russia had become public enemy Number One of the United Kingdom. From great ally of liberal England, the czar had become a barbaric, furiously expansionist despot. From then on, solidly implanted in public opinion, British Russophobia was rapidly going to translate into open warfare. A mere spark might start it.”(2) The cheerleader for British Russophobia, Lord Palmerston, described the struggle against Russia as a “fight of democracy against tyranny” (like British politicians today). The spark came in 1853. An argument over the rights of Christian minorities in Palestine, which was governed by the Ottomans, led to Turkey declaring war on Russia in October of that year. The Russians destroyed a Turkish fleet at Sinope, and the British and French, fearing a Turkish collapse, joined the war and invaded the Crimean peninsula. This war, the only time when British and Russian forces have ever clashed directly, was a watershed in Anglo-Russian relations and poisoned them for over sixty years. The first war that was photographed and reported in detail in the Press, its names and events, its horrors and heroes, victories and disasters, were imprinted on the national consciousness. Countless British street names across the country stem from it.

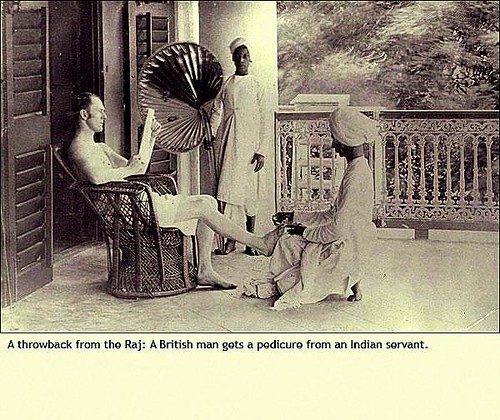

Britain’s embarrassments in the Crimean War and its subsequent defeats in colonial struggles in Africa only worried British imperialists even more over those six decades. Despite being at a peak of power at the time of Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, and despite their ever increasing imperial pride and bombast, the British elite knew the empire was fragile, both at home and abroad and that after the 1870s, it was losing out economically to Germany and the USA. Only two years after of the costly victory in the Crimea, the Indian Mutiny or Rebellion had broken out which deeply shocked the outraged British, put them very much on the defensive, aware of the Indians’ potential for further uprisings, and greatly increased their sense of racial superiority and psychological distance from the Indians: ‘the Club’ mentality now took over as the British community in India restricted itself more to its own circles.

Meanwhile, the Russians, laying railway lines now, advanced slowly but steadily in these decades across Central Asia from the Caspian Sea towards Afghanistan. As ever, the abiding British fear was the possible loss of India, the source of their national and personal profit, of their civilisational, cultural, religious, professional and racial pride, and of their lust for adventure and self-assertion. The 30-year period 1877-1907 was the high point of the Great Game, as the Russians inched ever closer to India. Disraeli declared Victoria ‘Empress of India’ in 1876, his friend Colonial Secretary Edward Bulwer-Lytton having nationalised the East India Company in 1858. Disraeli also appointed his friend’s son, another Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Viceroy of India under Victoria as Empress of India. In the same year 1876, a major famine broke out in India during Bulwer-Lytton’s viceroyalty; at least 8 million died and Bulwer-Lytton was much criticised for his poor response to the disaster, a response informed by his Social Darwinist views. In 1878 he took British India into the 2nd Afghan War, which was fought for much the same reasons as the first, and in 1879 the empire suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the Zulus in S. Africa, another Disraelian imperial ‘adventure’. These years were something of another watershed in British history; for the next 4 decades until 1914 British attitudes towards the Empire were marked by a peculiar hubris, as grandiose dreams of Imperial Federation (1884), a united globe-spanning imperial entity, arose in the imaginations of sections of the imperialist elite, led by the likes of Charles Dilke MP, the historian J.R. Seeley, Cecil Rhodes, Lord Milner and the journalist W.T. Stead.

But along with this growing hubris came a greater awareness of a gnawing weakness vis-a-vis Russia, Germany and America. This awareness led to the diplomatic revolution in British foreign policy that occurred between 1887 and 1907. A complex of factors crystallised in the years 1884-87 that there is not space here to go into, but perhaps the most significant of them was that in 1887 the British faced a looming Franco-Russian alliance in support of a potential Indian rebellion by the Sikh prince Duleep Singh (see pic below), who had been removed from India as a child by the British government and brought up in Britain. He had since rediscovered his Indian roots and wanted to return to India to lead his people in the Punjab. The British saw this as the most serious challenge to the British Raj: the prospect of an Indian rebellion aided by two major European Powers. They managed to weather the crisis, not least because the Czar Alexander III (1881-1894) refused to support Duleep Singh, but it led them to reassess their imperial strategy and foreign policy. They concluded that the joint threat from their long-term opponents France and Russia would have to be met by aligning with those two countries, and the price for this would have to be ditching Britain’s traditionally friendly relations with the enemies of France and Russia, namely, Germany and Austria.

Britain’s national myths

Before proceeding, a very important background motif to the Great Game and 19th century Anglo-Russian relations should be considered. By the end of the wars against Napoleon, Britain and Russia had already embraced their own very significant national myths, both of which, in their differing ways, harked back to ancient Rome. The British elite and many in the British population as a whole, since the country’s victory over Spain’s Armada in the 16th century – which was more of a lucky escape – and its humbling of royal and then imperial France in the 18th and early 19th centuries, its success in planting colonies in N. America and elsewhere, the growth of its overseas possessions, its commercial achievements safeguarded by the world’s greatest navy and supported by its scientific and technical progress and prowess in the burgeoning Industrial Revolution, had come to feel that Providence was now blowing in the sails of the British ship of state. Yet there was something of a split in English national consciousness in the late 18th century. There were those more cynical and self-interested, less concerned with saving their souls and more concerned with maximising their profits, whose values were more influenced by rationalist and classical Roman models. They regarded themselves as realists and ‘down to earth’ and wanted to ‘get on in the world’, whether at home or abroad. These people believed that they accepted the world as it is and sought to profit from it – as it is. One such was Robert Clive, the victorious general of the East India Company’s wars in the mid-18th century. He started in India in 1744 as an office clerk for the East India Company and finally returned home to Shrewsbury in 1767 a very wealthy man indeed, with the equivalent of about £50 million in today’s money, which he himself regarded as a moderate sum, he said, given the opportunities available in India for greater profit. Arguably, no-one did more to cement the structure of British power in India than Clive. Yet when he left India in 1767 he said: “We are sensible that… the power formerly belonging to the soubah [ruler] of those provinces is totally, in fact, vested in the East India Company. Nothing remains to him but the name and shadow of authority. This name, however, this shadow, it is indispensably necessary we should seem to venerate.”(3) This had also been the attitude of the rulers of the City of London, of whom the globally operative leaders of the East India Company were the foremost, towards the British monarch: to venerate the throne, safe in the knowledge that since the so-called “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 or even since the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the throne reigns but does not rule; we, the wealthy men of the City of London, rule. Such was the cynical attitude of the men of power. However, seven years after his return from India, in 1774, aged 49, Robert, now Baron Clive, an opium addict suffering from depression and gallstones, died after slitting his throat with a penknife, a victim of his own success.

From the time of the Elizabethan sailors and adventurers of the 16th century – ‘latter-day Vikings’ like Drake, Hawkins, Frobisher and Raleigh – Britain’s expansion had been driven by lust for profit, by curiosity and love of adventure; such was the case in England’s southernmost colonies in North America, from Virginia to the Carolinas, but there was also a particular religious motive – most evident in the more northern colonies, from Virginia to Massachusetts – namely, the desire of the Puritans to escape, like the Israelites on whom they modelled themselves, from the wickedness of sinful ‘Egypt’ (i.e. England) and seek their Promised Land in North America. Impressed by the Jews they had met in the Netherlands, the English Puritans in America increasingly came to see themselves as God’s new ‘Chosen People’. Though nominally Christians, they lived their lives especially according to the Old Testament, which meant that many of them, though not all, tended to regard the native peoples among whom they came as ‘Canaanites’, savages beyond God’s grace, who could and should be treated harshly, even genocidally if necessary, as Joshua did with the peoples of Canaan. However, from the 1770s onwards, a new religious movement – that of Evangelical Anglicanism – was abroad in Britain; it gave rise to a new form of the national ‘Chosen People’ myth, and its pietistic Methodist emphasis on the inner life and the new Birth in Christ and the Holy Spirit emphasised the New Testament rather than the Old, challenging the Established Anglican Church, in which many felt religiosity had become a matter of outer forms, ceremonies and compliance with social conventions. Many people were longing for a religious life of experience that emphasised high moral standards for both clergy and laity. The shock of the loss of the American colonies, Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which was published in the year of the American Declaration of Independence, the trial of Warren Hastings for corruption in the East India Company, the extravagant decadence of many in the upper class, the growing awareness both of the harshness of the Industrial Revolution and of the evils of the slave trade – all these filled many people with the notion that God was testing and punishing England for its sins. However, despite the new focus on the New Testament, on Christ in the individual soul, and on compassion for oppressed people and slaves, a new sense of conviction emerged among the English that they were after all, God’s Chosen People, a people whose destiny it was to be a light unto the world. ‘He who challenged God, challenged England’ and ‘he who challenged England, challenged God’. The English, it was felt, had been given the mantle of world power by God and must use it ‘properly’. They thus determined to keep that mantle as long as was ‘proper’ or as long as Providence decreed they should. The Evangelical Anglicans were very active in the anti-slavery movement, which eventually achieved success in the British Empire by 1833. As the Royal Navy patrolled the world arresting slave traders while keeping the oceans safe for British commerce, this gave liberal-minded people in Britain a smug sense of moral superiority, and gradually, the sense of divine entitlement with regard to the Empire, especially after the British State took over the running of India when the East India Company was nationalised in 1858. The mediaeval myth of St. George rescuing the maiden from the dragon came in very handy here to justify the actions of the Foreign Office. No longer was the empire merely a sordid source of profit and wealth, now it was felt, it also had to be a moral and providential crusade to ‘save benighted peoples from tyranny’ or to ‘elevate the natives’ in the Empire beckoned. Grand inflated perspectives of history and imperial destiny and mission loomed. It was now seen as Britain’s task to spread such things as freedom, parliamentary government, law, civilisation and Christianity throughout the world.

Something akin to the fate of ancient Rome occurred in 19th century Britain in its attitude to its empire: the conquests of the Roman Republic had been a no-nonsense, down-to-earth enterprise of straightforward military might, to destroy rivals in the name of survival or to punish recalcitrant client rulers, or else simply to acquire more territories for taxation and mining. The Roman Empire, however, became increasingly pompous and pretentious, less Roman and more Greek and Asiatic in its attitude and values as time went on. A similar transition also happened in 19th century Britain and was reflected in its frequent poor military showing in the second half of the century. The hardnosed harshness of British life in the Napoleonic period and the plain, classical lines of Georgian buildings gave way to a ‘softer’, more Romantic image presided over by that essentially middle-class couple Queen Victoria and her consort Prince Albert, while their people, or those who could afford it, indulged themselves in nostalgia for the chivalric Middle Ages and the Gothic style, which reflected the ‘new’ Romantic sensibility in the arts and architecture. Or else, as so-called ‘scientific’ racism began to take hold after the 1820s and 30s, other Britons fancied themselves the literal descendants of the ancient Israelites who, it was said by the new British Israelite movement, had wandered from the Holy Land in the form of the Ten Lost Tribes of the Old Testament over to Europe, to northern Germany and Denmark, from where they had settled in England and produced the British Royal Family! Much taken with this idea, Victoria and Albert even had their royal male children circumcised, and royal male heirs apparently continued to be circumcised until the late Princess Diana put her foot down. While the symbol of Britain in the first half of the century was more the self-satisfied, materialistic, down-to-earth yeoman squire John Bull, in the second half it was more the refined image of the quintessential English gentleman, or else the allegorical figures of Britannia and the British lion.

Rudolf Steiner gave a humorous description of this process in a lecture in February 1920, at which a number of English people were present. He spoke, with considerable irony, of how the empire began with “adventurers, considered rather undesirable at the heart of the empire” who went out to make their fortune and then came home with their wealth. Society looked askance at them but their sons and grandsons ‘smelled’ a little better: “And then empty words take over the thing that is beginning to smell nice. The state takes everything under its wing, becomes the protector, and now everything is done in an honest way. It would be good if we could call things by their proper name, but the proper name very rarely denotes the actual reality.”(4) He was speaking in that lecture about the three periods of imperialism that had developed over the past 5000 years or so. First, there had been theocratic, priestly empires ruled by demigods, god-kings; then military empires ruled by the aristocratic warrior class in which the rulers were no longer god-kings but symbols ruling by divine right on behalf of the deity; this was already a step down, so to speak; and then finally, since the 16th century, economic empires based at first on trade and stealing other people’s land, but which were then embellished, prettified, ‘tarted-up’ we might even say, with fine, empty words to make the economic empires less, well, embarrassing. Today, we see this same thing in institutions such as the World Economic Forum or in the foreign policy statements of modern governments, and, some would say, especially the British government, where over the past two centuries, hypocrisy has been made into an art of sorts.

Russia’s national myths

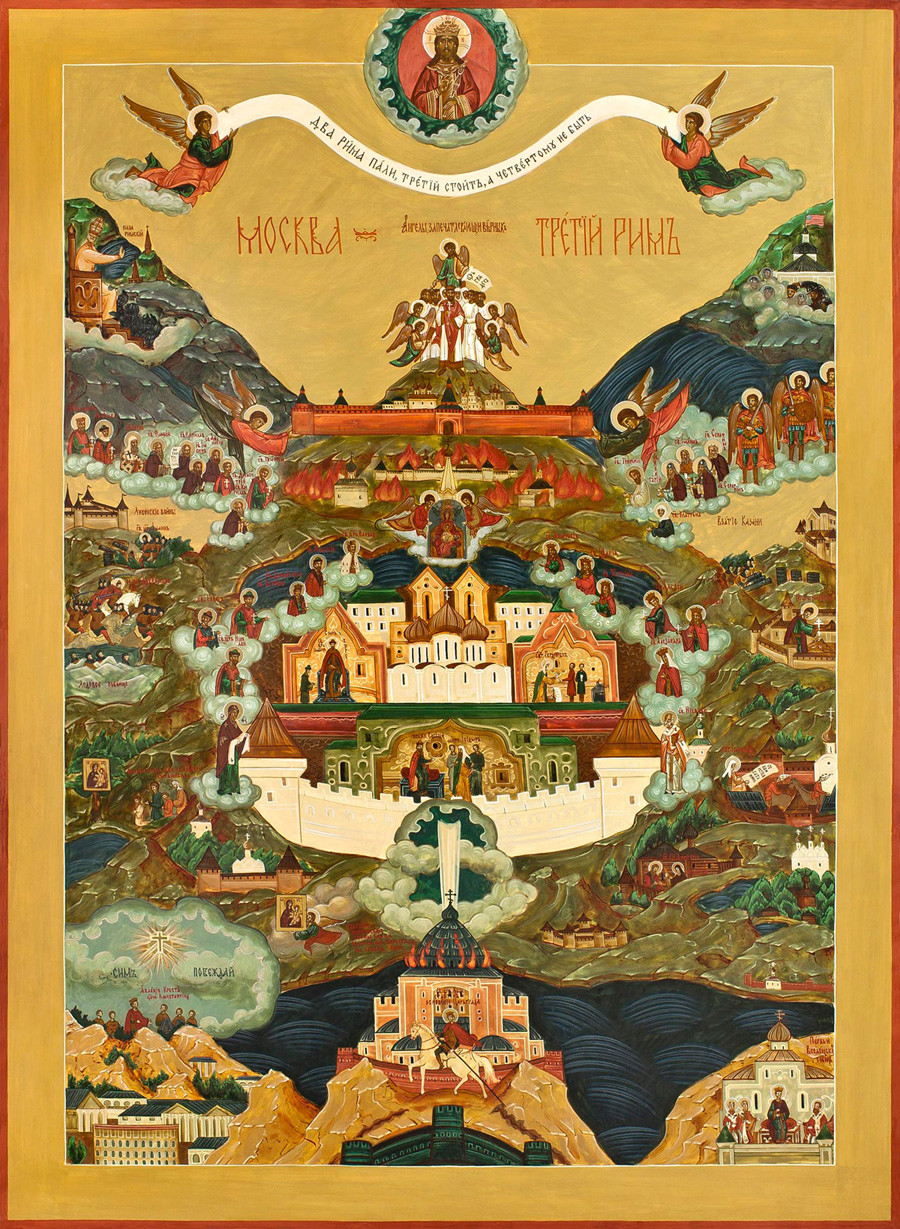

Russia, meanwhile, had developed two national myths of its own, one from the past and one from the present. The myth from the past, from the Greco-Roman Byzantine age of Constantinople, was that there had been the first Rome and it had fallen in 476 AD to the Goths and had been replaced by the second Rome – Constantinople – and this too had fallen, in 1453, to the Turks and it had been replaced by Moscow, which had taken on the mantle of Orthodox Christianity. According to this idea, which emerged in Russian ecclesiastical circles towards the end of the 15th century, Moscow had become “the Third Rome”, as Metropolitan of Moscow Zosimus expressed it in 1492 and called Ivan III “the new Czar Constantine of the new city of Constantine — Moscow.” The monk Philotheus wrote in the early 16th century: “So know, pious king, that all the Christian kingdoms came to an end and came together in a single kingdom of yours, two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and there will be no fourth. (5) [emphasis added]. No one shall replace your Christian Czardom according to the great Theologian” [i.e. St. John the Apocalyptist]. (see pic below) This must have made Russians feel that their country was in some way divinely sanctioned. The Russian Czar – the very name of course comes from ‘Caesar’ – was thus the protector and father of all Christians just as the Byzantine Emperors in the 1000 years after Constantine had regarded themselves. The Patriarch in the Orthodox Church was always subordinate to the Emperor, unlike the Roman Popes, who regarded themselves as above kings and emperors and who until the 1860s were territorial rulers in their own right. Consequently, the impulses of the Russian State were regarded as at least semi-religious in nature, when for example, Russia sought to push the Ottoman Turks out of Crimea or the Balkans. It regarded itself as the Christian Orthodox patron of the southern Slavs.

Furthermore, from the early 19th century onwards, as doctrines of nationalism and racialism began to spread from western Europe and were picked up in Russia, another national myth emerged – the idea of Pan-Slavism in two forms, notably in a Russian imperial, conservative, traditionalist form (as promoted by the Savoyard diplomat Joseph de Maistre, who lived for many years in Russia and exercised a considerable degree of influence as well as in a republican nationalist form.

Pan-Slavism and the Hatred for Russia

This secular nationalist Pan-Slavism was supported by the British elite, as we can see from the book The Ottomans in Europe (1876) by the Turcophile British historian John Mill (Nb. not the philosopher, economist and Member of Parliament, John Stuart Mill). This book gives us a vivid idea of the degree of sheer hatred of Russia that had built up in England in the 19th century (and which is still expressed, albeit rather less viscerally, in the British media today through the regular, Orwellian ‘anti-Russia, hate Putin’ propaganda slots on BBC news and current affairs programmes). After praising the Turks to the skies as “the Englishmen of the East”, Mill says of the Slavs:

“The Slav is almost the greatest failure nature ever made in her attempts to create a civilised man. …. The prime cause of Russia’s weakness lies in the innermost core of the Slav heart. It is void of truth, and this want of veracity threads its rottenness into every department of the State…” […] “For many years past Russia has been, like one of the magicians which we read of in the books of the Occult Brethren, who ‘call spirits from the vasty deep’, with this shade of difference, that they called those they could master and allay. She, by her greed, rapacity, and brutal lusts, has awakened demons which she is quite unable to control. They have taken possession of her body and soul, and they are all imps of blood.” [….] “Russia is…the land of hatreds; of mistrusts, of brutal force, and abject cowardice; of profuse waste in some parts of the public service, of galling wretchedness in others. …The conviction has sunk into the pale, wan heart of Russia that she cannot be worse, and although the Emperor and his party, to some extent, guide and curb the military passion, and keep the peasantry in subjection, this cannot last long; the bloodhounds will slip the collar sooner or later, and then will the cry of ‘havoc’ arise…..” “The Eastern Question has to be solved in blood. It is simply a series of surgical operations, which will have to be performed with more or less skill, and the final question is which of the parties upon whom the amputations are to be performed can best endure the depletion. There are three: Russia, Austria, and Turkey who must go into the operating room; others, especially England, may be dragged in, but for the three former, there is no escape.” […] “The solution, then, or rather the dissolution, of Russia, is the real Eastern Question….it is rather a Northern than an Eastern question.” (7) (emphasis TB)

One can find equally racial invective against Russians and the Slavs in general in the writings of Karl Marx when he was in Britain and collaborating with another inveterate Russophobe, David Urquhart (1805-1877), diplomat, writer and politician, (see pic below) who single-mindedly devoted some forty years of his life to pro-Turkish and anti-Russian propaganda, including starting a newspaper for the purpose, and writing endless articles and letters to the Press.

.jpg/450px-David_Urquhart_(1805-1877).jpg)

Mill and those in Britain who thought like him, and they were many, was thus concerned to bring about the break-up of the Russian Empire for the sake of preserving the British Empire of which he and they were immensely proud. We should bear in mind that the only reason that Britons such as Mill actually cared a jot about Turkey is because they regarded it as the gateway to their Raj in India, a gateway they were determined to keep shut to challengers.

Similarly, today it is improbable that the likes of UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace and recent British Prime Ministers Boris Johnson, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak care a jot for Ukraine, but they doubtless regard it, as do the higher level geostrategists of the West, as the instrument with which the West can hammer at Russia as well as the channel through which, having failed in Central Asia between 2002 and 2021, the US and UK can hope eventually to penetrate back into Central Asia, as Zbigniew Brzezinski advocated (8). Britons “in the know” in the 19th century, such as John Mill may well have been, were seeking to use what they called republican nationalist Pan-Slavism as a hammer against what they called Russian imperial Pan-Slavism. Republican nationalist Pan-Slavism could, they imagined, be used to draw Russia into a major war with Germany and Austria, a war which would result either in the break-up of the Russian state or in a Communist takeover of Russia, which might also, through civil war, end in the dissolution of Russia. Mill’s book contains maps of future plans for Russia, eastern and central Europe – maps which, he said, were circulating in secret societies that served Russian imperial aims as well as others that revealed the goals of secular nationalist and republican Pan-Slavists such as the Narod Odbrana and Omladina organisations, (9) which represented the nationalist republican heritage of the French Revolution. For the latter groups’ goals to be realised, however, the traditional alliances, friendships and enemies of Britain and France would have to be reversed. Britain’s traditional enemies – France and Russia – would have to be brought together in opposition to Germany and Austria so as to encircle the Central European Powers. And all these remarkable things, hardly conceivable in the 1860s, were actually achieved in the diplomatic revolution mentioned earlier, which was driven through, step by step, between 1887 and 1907, so that by 1907, the Triple Entente of Britain, France and Russia faced off against Germany, Austria and nominally, Italy. That diplomatic revolution led directly to the First World War seven years later in 1914, a war which began in Bosnia over the issue of Serbia’s nationalist Pan-Slavism which wanted to see a federation of all the South Slavs under Serbian leadership. This was opposed to Russia’s Imperial Pan-Slavism and its still burning desire to recover Constantinople for the Orthodox faith and its own ‘Christian Empire’.

In Ukraine today, the British and Americans have been using the strategic playbook of the late Polish-American geostrategist Zbigniew Brzezinski to manipulate similar Slavic ethnic hatreds in order to draw Russia into another long war with the intention, as in 1914, of ruining her again. The difference between Russia in the situation of 1876 that Mill was writing about and Russia in 1914 is that by 1914, Russia had developed into a Great Power that both the British and German elites now saw as a major threat to the survival of their own empires. The British were more concerned than ever, as usual, for the survival of their control over India and their world empire as a whole; as Lord Curzon, the Viceroy in India, said in 1901: “As long as we rule India, we are the greatest power in the world. If we lose it, we shall drop straight away to a third-rate Power”.(10) The German Foreign Ministry, aware of the Russian Empire’s own Pan-Slavist ambitions, understood that Russia regarded Germany and its allies Austria and Turkey as standing in the way of those ambitions, which centred on recovering Constantinople and controlling the Balkans. What the Russians likely did not suspect was that their British ‘allies’ in the Triple Entente were actually planning a war that would destroy, break up, or severely weaken Russia. American historian Sean McMeekin in his book The Russian Origins of the First World War (2011) was right to point the finger of blame at Russia for turning what could have been just a third Balkan war into a pan-European and world war, but what he failed to see, or did not want to see, was that it was the British, concerned for the survival of their world empire that depended on control of India, and the French, still burning for revenge over the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany in 1871, who had for nearly three decades been the two main forces driving the unfolding tragedy that began with the assassin’s bullets at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. The Germans, Austrians, Russians and Turks all ended up in Mill’s “operating room” for “amputation” as the victims of this Anglo-French paranoia and revanchism.

In 1993 a book was published that bears out the British intentions only barely masked by John Mill in his 1876 book The Ottomans in Europe. The subtitle of that book was “or Turkey in the Present Crisis, with the Secret Societies’ Maps”. According to Mill, those secret societies were the political secret groups that stood behind the Pan-Slavists, namely the republican Pan-Slavist Omladina group, which represented the nationalist republican heritage of the French Revolution, and also the secretive groups that backed Russian imperial Pan-Slavist goals. The 1993 book was The Transcendental Universe by Charles G. Harrison – a collection of six profound lectures on occultism given by Harrison a hundred years earlier in 1893. He predicted “the next great European war”, “the death of the Russian Empire so that the Russian people could live” and also that “the national character [of the Russians] will enable them to carry out experiments in socialism, political and economical, which would present innumerable difficulties in western Europe.” (emphasis TB)

This is what John Mill meant in his 1876 book when he wrote: “if an army of the Emperor [of Russia] should ever fall into another Sedan beyond the Danube, a Commune would very soon be declared in Moscow.” (11) The expectation in occult and political circles in Britain was that communism would soon be coming in Russia and that the West would bring it about. Because of his friendship with Friedrich Eckstein, who was an internationally active Theosophist with his finger on the pulse of what was going on in esoteric circles in London in the 1890s, Steiner was very aware of this agenda at which Mill had hinted and Harrison had stated more clearly. Steiner felt that if people don’t wake up to the lies and deception with which the elite forces of the West must operate, the consequence will be terrible suffering and violence until those elites’ actions are overcome through impulses that stem from the Germanic and Slavic cultures. (12)

On 22 December 1900 in the American magazine The Outlook, readers were told that “the true statesman looks to the future. It is clear to one who does thus look to the future that, as the issue of the past was between Anglo-Saxon and Latin civilization, so the issue of the future is between Anglo-Saxon and Slavic civilizations. [...] The wise statesman will make every provision possible by establishing cordial relations between all the kindred races for the final victory of the Anglo-Saxon type of civilization.”(13) Today in Ukraine, in another proxy war, we are witnessing that struggle between the Anglosphere and its client states on the one side and Russia (and perhaps China too) on the other.

The last article in this series (http://threeman.org/?p=3104) will consider the Anglo-Russian antagonism from 1900 until today.

Endnotes

1 Markus Osterrieder, Welt im Umbruch (2014) p. 927.

2 G. Mettan, Creating Russophobia, p. 191.

3 “Clive, Robert Clive, Baron, Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 532–536.

4 Lecture of 20.2.1920, Dornach in Ideas for a New Europe (Rudolf Steiner Press) 1992, pp 57-58.

5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moscow,_third_Rome

6 For illuminating insights into the character of de Maistre, see lecture by Rudolf Steiner, 1 May 1921 in Materialism and the Task of Anthroposophy (RSP, 1987).

7 John Mill, The Ottomans in Europe or Turkey in the Present Crisis, with the Secret Societies’ Maps (1876). The full text is available to read at archive.org

8 Z. Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard (1997) see chaps. 4 and 5.

9 Rudolf Steiner discussed such groups at some length in his lectures of 9,10,11 Dec. 1916, in The Karma of Untruthfulness, Vol. 1 (RSP) 2005.

10 In Nicholas Mansergh, The Commonwealth Experience (1969), p. 256.

11 A reference to the Battle of Sedan, a major French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.

12 For the full Steiner quote, see my article ‘The Anglo-Russian Antagonism Part 1’ in New View #104 July-September 2022, p.17.

13 Markus Osterrieder, Welt im Umbruch (2014) p.928.

Terry M. Boardman