The 1960s: a Generation’s Path through Will, Wisdom, Love and Illusion.

Posted by Terry Boardman on Dec 15, 2024 in miscellaneous, most recent, Uncategorized | 0 commentsThis article was first published in New View magazine #112 Summer 2024

We are now perhaps far enough away from the 1960s to be able to look back on that decade – and many of us are still alive who can remember what it was like to be young at that time – and realise that it was a time that is extraordinarily pregnant with meaning and vividly illustrative of the contemporary spiritual struggles going on then, which in many ways prepared and seeded the ground for much, though of course not all, of what is occurring today. After all, 63 years ago, in 1961, when the Berlin Wall went up, was a time when Cold War tensions began to peak – just as they are doing today. That decade began in the year that JFK arrived in the White House, the “winds of change” began to blow in Africa, the Vatican II Council was underway, the war in Vietnam worsened, the Berlin Wall went up and Europe was definitively split in two.

But then, despite those tensions, the 1960s were also a threshold moment when, as it were, in just a very few years, a new young generation responded to those tensions by brusquely pulling back a curtain, and a different world – of freedom, equality, brotherhood, love and peace – was suddenly glimpsed by many, whether with or without the use of ‘stimulants’. Many reached out to grasp or realise that vision of a different world, but it soon slipped between their fingers; the curtain closed again and the vision blurred over. By 1973 certainly, it was no more. Perhaps not since the spring of 1848, that year of liberal revolutions across Europe, had so many people, especially in the younger generation, in many countries, suddenly and dramatically sensed the possibility that the world might so unexpectedly change for the better, in a way that was similar to what happened in the mid-late 1960s. Of the atmosphere of 1848 the German historian Karl Heyer wrote: “A wonderful atmosphere must have prevailed, especially in Germany, beginning with those splendid spring days in March 1848. A breath of liberation passed throughout society, emanations of the strongest feelings, borne by a tremendous enthusiasm, of the will to sacrifice and devote oneself to an ideal of life, permeated by rapturous feelings, and the hope, indeed, the subjective conviction: now everything must get better! ‘My heart feels warm whenever I recall those days’, wrote Carl Schurz (1829-1906) later in his memoirs; he had taken part in the events of the year of revolution, then went to America, where he became a significant American statesman. He especially emphasised the willingness for sacrifice which had then gripped countless people of all kinds. Friedrich Payer, born in 1847, who still strongly felt the afterglow of the year of ’48 in his youth, thought in his old age that the expression ‘the Peoples’ Spring’ most resembled what the German people were experiencing at the time, namely, that it was like a proliferation of the feeling which young people felt awaken in themselves when the oppression and night of winter gives way to the bright, warm spring sunshine. ‘There must be something glad and victorious in the air’, a feeling that in a miraculous way renewed itself for months on end…”1 There had also been a comparable upsurge in enthusiasm in America in the mid-1770s and in France in 1789-90, but those upsurges had only occurred in two countries. In the 1960s, the feeling of tremendous change in the air was more worldwide, from Japan and China, across Europe and right across N. America as far as California.

The forces demanding cultural and political freedom in Europe in 1848-49 were harshly suppressed by the powers of Old Reaction – monarchy, aristocracy and the Church – in most cases supported by the power of the banks. Liberalism failed in the second half of the 19th century, and new, poisonous forms of politics arose to challenge the old conservative forces that would not and could not yield: radical nationalism, fascism and communism. These challenges shattered Europe in the first half of the 20th century, but even after the world wars, and despite all the guff about the movement for European unity, 100 years on from 1848, forces opposed to real change in Europe had not shifted; they had only put on new authoritarian masks: monarchy, aristocracy and the Church may no longer have had the power they exercised in 1848, but in their place, or alongside them now in 1948 were Big Business, Big Finance, Big Science, Academia, the Establishment-buttressing mass media, and the new, sinister intelligence agencies of the centralised, modern Big State.

Rudolf Steiner had said in 1919: “if the teaching at our universities goes on as it does now for another 30 years, and if people continue to think about social matters in the same way for another 30 years, then, by the middle of this century, Europe will be a desert…everything will be in vain if there is not a fundamental transformation in human souls in the way they think about the relationship between this world and the spiritual world. If nothing is learnt anew in this sense, if people do not reshape their thinking, then a moral deluge will engulf Europe!…[the] middle point of our century coincides with the end of the period in which the forces from before the middle of the 15th century – still atavistically with us to some extent – reach their ultimate decadence. By the middle of our present century [1950s] mankind must have taken the decision to turn towards the spirit… new forces must be drawn up from the depths of human souls…”.2 The decadent “forces from before the middle of the 15th century” that Steiner was referring to were the forces of the previous Greco-Roman epoch, its politics, legalism, and academic intellectual thought, as well as the forces of Old Testament Hebraic culture carried by church dogmatism, and also ancient pagan sentiments and values from pre-Christian times. But teaching had not essentially changed by 1950, nor had social thinking, nor had there been any fundamental transformation or turn towards the spirit before the beginning of the 1950s, and the result had been that Europe had indeed become a physical ‘desert’ in many areas in the 1940s. For many younger souls who had been born during the war or in the postwar years it remained a psychological desert in the 1950s.

The three waves of the 1960s

But then came the great shift of the 1960s as those born into the chaos of the war years reached adulthood. The shift occurred in 3 discernible phases that bore some resemblance to what happened in France (and to an extent elsewhere in Europe) from 1780-1815 as the classical Enlightenment era gave way or was overlapped by the newer, Romantic sensibility.

First, there was a wave of enthusiasm for all things in areas of scientific and technological knowledge; this was driven by the Establishment and its media instruments to a large extent, as it depended greatly on high finance. Something similar had happened in the 1780s, when Europeans were fascinated by new scientific ideas and technological fads and developments, including: hot air balloons, steam cars, electricity, mesmerism.

The elegant ‘modernist’ look of the early 1960s

In the early 1960s high employment, consumer goods such as TVs, transistor radios, and motor cars and improved transport links such as motorways generated great enthusiasm that was boosted by the new satellites and rockets to ‘outer space’, the new shiny skyscrapers going up around the world with their abstract, scientific, Modernist designs that were soon echoed in the sleek lines of young people’s fashions and hair styles. Politicians indulged in rhetoric about changing society in “the white heat of the technological revolution”. But all this was not yet a protest, an effort to transform fundamentals, let alone those of a spiritual nature. It was more a consequence of the confluence of growing prosperity plus the percolated effects of the first Modernist wave in art and design that had begun around the time of the First World War some 50 years earlier and had been ‘held up’, as it were, for a generation by the two world wars.

However, this first, rather ‘top-down’ level of knowledge and science-based cosmetic change which saw the sleek style of the early 1960s already looking very different from the dowdy early 1950s, was followed by a ‘bottom-up’ movement of social imagination and feeling as millions of the new baby-boomers became involved in campaigning activism, first against the horrors of nuclear weapons and then inspired by the civil rights movement in the USA and the worsening Vietnam war situation, confused and disturbed by the assassination of US President Kennedy in November 1963 and the feeling that perhaps, somehow, the Establishment had killed one of its own, who had yet seemed to be the ‘people’s tribune’. After the killing of Kennedy (followed by other assassinations of prominent popular leaders such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and President Kennedy’s brother Bobby), the USA soon began to slide into psychological disequilibrium and growing tension and trouble between the generations, the races, and within families. France had been the stoker of protest in the period 1770-1870, but the USA has largely filled that role since 1945 and certainly did in the 1960s. In the 1950s there had been no great youth movement in the West in support of the Vietminh struggle against French armies, but by 1960 the ‘baby-boomer’ generation3 had come of age in consumerist America; it had not previously needed to fight in wars or hustle for its economic survival like previous generations; it was ‘literate’ and its students had time on their hands and money in their pockets. Born into the terrible strife of world war and the social problems that followed, the indignation of this generation over the racist civil rights abuses in their own country still going on 100 years after the US Civil War was combined with what they saw as yet another imperialist American war overseas, in Vietnam and the stultifying consumerism and materialism of 1950s America. By the mid-60s, political activism and campaigning among both black and white youth was becoming a matter of serious concern to the Establishment.

Civil Rights march mid-60s USA – Martin Luther King and Coretta King

This second aspect of the 1960s, that of a social and political activism that owed much to older traditions of collective social action over the previous 100 years, lasted until approximately the middle of the decade, by which time it was being overlapped and increasingly infiltrated and ultimately weakened by the decade’s third wave or aspect: a very new, individualistic, hedonistic and also more anarchic, self-conscious cultural movement that was concerned above all with personal development but in a ‘new’, ‘tribal’, collective context, which came to be called “flower power” and from 1965, was centred on LSD and other hallucinogenic substances. Scott Mackenzie (1939-2012, b. Philip Wallach Blondheim III) – one of the instant troubadours of this cultural new wave that was soon recognisable by its oriental and tribal fashion statements, its long hair for both men and women, its headbands, flowers, bells and sandals – sang the song which in May 1967 became the anthem for the hippie ‘movement’: “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair)”: “All across the nation, such a strange vibration, people in motion. There’s a whole generation with a new explanation….people in motion.”

The Summer of Love 1967, USA

Many people have written4 about how the second, ‘political action’ wave was either partly or substantially subverted by government agents behind the scenes in order to weaken and undermine the political activism of the second wave. These agents seeded young people’s communities with mind-altering substances such as LSD and the ideas of Pied Piper Establishment scientists such as ‘acid prophet’ Timothy Leary and his colleague Richard Alpert (aka Baba Ram Dass), A turning point here was the much-hyped first “Human Be-In – a Gathering of the Tribes” at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park on 14 January 1967, which began with the words: “Welcome to the first manifestation of the Brave New World”. The main speaker at the “Be-In” was the self-appointed guru of the new psychedelic movement, Timothy Leary, who urged the assembled 25,000 young people to “turn on, tune in and drop out”. What those in the park did not know was that the event was the brainchild of veteran American occultist John Starr Cooke,5 who lived in wheelchair-bound seclusion in Cuernavaca, Mexico, and of his artist disciple Michael Bowen, who had moved to the ‘hippie central’ Haight-Ashbury area of San Francisco at Cooke’s request in order to stimulate the ‘Brave New World’ by organising the “Human Be-In”.

This is not to say that the whole of the 60s or the whole ‘flower power’ hippie movement, which looked so much to Asia and to other non-western cultures for inspiration and spiritual guidance, was a mind control operation run by the CIA or other ‘occult’ (i.e. forces hidden behind the scenes), as has often been argued online over the past 20 years or so. It’s not difficult to trace the many orientalising influences present in the western states of the USA, notably California, that had been growing there especially since the first World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, held 11-16 Sept. 1893. These influences permeated a not insignificant part of the ‘baby boomer’ generation. “There was a fantastic universal sense”, wrote Hunter S. Thompson6, “that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning …And that, I think, was the handle – that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting – on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave.” This optimism and confidence were similar to the mood of the “Peoples’ Spring” in 1848.

However, by the end of 1969, after the Woodstock festival and the Manson murders in the summer of that year (both in August), the mass murder of over 400 students in Mexico City in October, the murder at the Altamont rock festival in December, and the worsening hard drugs situation in San Francisco, the hippie dreams of 1967 had already darkened. Many sensed that the dream was already dying, or even dead.

Music reflected this darkening and turning inwards; although musical creativity in the pop, rock and jazz scene was truly remarkable between 1963 and 1973, and affords real insights into the very wide spectrum of ‘spiritual’ and cultural influences at work7 in popular consciousness in those 10 years, rock music in general got heavier, louder and darker, more ‘Gothic’ in the Romantic sense, driven both by technological ‘advances’ and ever-increasing indulgence in drugs and alcohol. One can compare a gentle idealistic song like San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair) by Scott McKenzie in 1967 with a hard rock number about a heroin dealer, The Pusher, by Steppenwolf in 1969, just two years later. One saw more and more people at festivals and rock music gigs who, either ‘high’ or ‘heavy’, were obviously out of their minds in one way or another. Indulgence in sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll had become the unholy trinity for all too many in this generation; its children would often have to pay the price in the coming years in terms of the broken minds and relationships of their young parents. It was as though an entire generation had embarked on a spiritual quest without fully realising it – and the ‘initiation’ had failed.

A failed initiation?

One of the first late 60s British rock bands I saw play live, Jethro Tull (see pic below) , had a hit song called Living in the Past in 1969. The lyrics speak of a hedonistic love affair between two people who choose to ignore those around them who are concerned about wars, disasters and revolution: “We’ll go walking out while others shout of wars, disasters… . Once I used to join in, every boy and girl was my friend. Now there’s revolution, but they don’t know what they’re fighting. Let us close our eyes. Outside, their lies go on much faster. We won’t give in, let’s go living in the past”. Jethro Tull’s visual image was also of a Pied Piperish nature, with Ian Anderson, their seemingly half-crazed flame-haired singer and flautist stalking around the stage dressed in a motley jacket with tails.

The band and the song very much evoke a harlequinesque Romantic sensibility that spoke to many of the later baby-boomers who preferred not to commit to social activism on a mass scale but at most, tried to set up small-scale communities of friends who had all more or less “dropped out” of conventional society, rejecting the conventional mores of the first half of the 20th century altogether. Inspired by the Beatles’ odysseys to India or contemporaries’ trips to the Himalayas or Latin America or any non-western culture, these young people, encouraged by the likes of older ‘wayfarers’ such as the Americans Timothy Leary (1920-1996) and Baba Ram Dass (aka Richard Alpert, 1931-2019), and the English ‘Zen’ philosopher Alan Watts (1915-1973), imagined they wanted to turn their backs on the West and on its religion and culture completely, seeking either to create their own from scratch, or to emulate, to a greater or lesser degree, some non-western village or tribal society. Such efforts had nearly all failed by the early 70s, like the manic ‘Family’ project of the multi-murderer Charles Manson, which ended in ghastly scenes like something out of Goya’s more nightmarish paintings, and those ‘communes’ that managed to continue, did so because, like the communities of gurus such as the Indian Bhagwan Sri Rajneesh (later known as Osho) and James Edward Baker (Father Yod) they were held together by the ‘iron butterfly’ discipline of a more or less authoritarian guru figure to whom all looked up and on whom they had become psychologically dependent to a greater or lesser extent.

The arrest of Charles Manson (kneeling) and his “Family”

Just as the Romantic generation of the period 1790-1840 looked to Ossian’s8 Celtic stories of ancient times or to Rousseau’s evocation of the non-European ‘noble savage’ living in harmony with nature far from the urbanised intellectual artificiality of European salons, palaces and gardens, many baby-boomers sought what Terence McKenna (1946-2000) later dubbed ‘the archaic revival’. McKenna was one of the more deep-thinking among them.

A psychedelic explorer and ‘philosopher’ and the man who Timothy Leary, with characteristic ‘modesty’ called “the Timothy Leary of the 1990s”, McKenna felt western culture was deeply sick and was trying to heal itself by returning to ‘neolithic values’, among which he included: “surrealism, abstract expressionism, body piercing and tattooing, psychedelic drug use, sexual permissiveness, jazz, experimental dance, rave culture, rock and roll and catastrophe theory”9, in other words, anything which inclines towards the breakdown of concepts and forms of space and time -

a kind of cleaning of the cultural slate, “getting back” to an imagined ‘Year Zero’, regarding everything in the evolution of the West over the past 5000 years as a mere bubble or an error in comparison with the wonder of a butterfly or a single psilocybin mushroom. Critical of the New Age movement of the 1980s, which he saw as a sham, McKenna wrote: “The New Age is essentially humanistic psychology ’80s-style, with the addition of neo-shamanism, channelling, crystal and herbal healing. The archaic revival is a much larger, more global phenomenon that assumes that we are recovering the social forms of the late neolithic, and reaches far back in the 20th century to Freud, to surrealism, to abstract expressionism, even to a phenomenon like National Socialism which is a negative force. But the stress on ritual, on organized activity, on race/ancestor-consciousness – these are themes that have been worked out throughout the entire 20th century, and the archaic revival is an expression of that.” 10

Many in this Romantic third wave of the 1960s, the ‘flower power’ ‘love and peace’ hippy sub-generation and its adherents and fellow-travellers, did indeed try to ‘turn to the spirit’ and seek to transform their souls by ‘drawing up new forces’ but all too often they did so not by ‘reshaping their thinking’ as Steiner would have urged, by morphing their modern intellectual thinking into what he saw as three higher, developmental forms of consciousness – Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition11 – that would eventually, if pursued diligently and patiently, enable them to perceive in the spiritual world. Instead, and usually not knowing about his ideas, they chose not so much to transform themselves as to trance-form themselves by not thinking at all – by becoming en-tranced, deliberately losing their heads, by giving their bodies and their heads over to modern synthesised drugs or ancient organic mushrooms or other hallucinogens and by using the massive force of technology via hugely amplified music, to overwhelm their thinking minds and push their bodies into movement. Change agent Timothy Leary said of himself and his fellow ‘turned-on’ academics: “we saw ourselves as unwitting agents of a social process that was far too powerful for us to control or to more than dimly understand.”12 The young generation in the 1960s had become, as modern people, so alienated from their own organisms that they were prepared to subject them to any mis-or maltreatment for the sake of ‘getting high’, ‘far out’ or ‘out there’. And certainly, many of them did so, a number were indeed psychic explorers in this sense who came back changed for the better, but others were lucky to survive and lost friends and loved ones who did not. Many had their sense of themselves shattered by the experience and in many cases, never recovered, or else they moved on to harder drugs, addiction to which eventually destroyed them. Steiner had commented 120 years earlier that those who sought to cross the threshold of the spiritual world, to “break on through to the other side” (as Jim Morrison put it in one of The Doors’ famous songs, Break On Through, 1967) under the impact of drugs or mystical spiritual exercises that did not work with clear thinking, actually ‘broke on through’ not to the objective spiritual world but to the inner world of their own organism, their own body, which was of course deeply conditioned by their own karma, the state of their own minds, which is why so many had such different experiences on drugs.

They took such risks with their bodies because they were so distrustful of western intellectual thinking, the thinking they’d been educated in, the thinking their culture was permeated with, and because – despite two world wars and the deaths of millions – the culture had failed to make the change referred to earlier by Steiner in 1919 – the need to draw new forces from the depths of human souls. They therefore opted to throw out the baby of thinking together with what they regarded as the dirty bathwater of intellect. They opted to go “living in the past”, trying to return to ancient modes of thought and life, whether those of their own culture (e.g. ancient Celtic or Scandinvian, Slavic) or of completely alien cultures in McKenna’s sense of ‘archaic revival’. Alien, that is, in this lifetime. It is always possible, after all, that some of these people were in fact reincarnated tribal people from non-western cultures or else a pre-Roman European tribal culture, trying, in a modern context, to ‘get back to where (they had) once belonged’, as “Get Back”, the famous Beatles song of 1969, puts it.

Will, Wisdom, Love

The young people of the 60s did this in one of two ways, depending on their personal karmic history: the outer path of union with the gods of outer nature (which Steiner called the northern or Apollonian path) or the inner path of union with the gods of the soul’s inner depths (the southern or Dionysian path). Some of them tested themselves on both paths. Ancient India, Steiner tells us, was a culture in which both paths were in balance, while ancient Persian culture with its worship of Ahura Mazdao was of the macrocosmic, northern path and ancient Egypt looked to find Osiris and Isis on the microcosmic, southern path.13 It is fascinating to see how in the 1960s some young western people sought the spirit by testing themselves in outer nature, by outer travel in dangerous and unfamiliar conditions, experiencing mineral, plant and animal life, mountains, deserts, ice floes and glaciers, jungles, while others tested themselves not in nature but through intense inner meditation, whether through drugs, through guided or self-taught meditative praxis or through artistic exploration.

Another polarity which they explored was that of Will versus Wisdom. The path of Will is that of the will of God as revealed in the world outside the human being, whether in the forces of Nature or through the outer commandments of a human leader. Young western people in the 1960s were aware of this path through what they could see in film recordings or movies of the mass movements of the 1930s – the Nazis and the Communists and also their contemporaries in Communist China waving their Litte Red Books with the thoughts of Chairman Mao Ze Dong – or else they obediently followed guru-like figures in their own societies, such as Malcolm X, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (of the Hare Krishna movement), Anne Hamilton-Byrne (The Family, Australia). The inner path of Wisdom in the 1960s was either that of inner exploration of one’s own organism through drugs, or else through guided meditation in the context of an oriental spiritual discipline such as Zen, Tibetan, or Theravada Buddhism. Steiner, in his 1914 lectures on Christ and the Human Soul (Collected Works GA 155) contrasted these two paths of Will and Wisdom with the path of Love, which is that followed by deepening one’s relationship to Christ within one’s heart. Steiner describes how the Hebrews experienced Will through the burning thorn bush and through the Ten Commandments given to Moses and the 613 rules for life given in the Hebrew Bible. Pre-Christian pagan cultures experienced Wisdom through the ritual processes of the Mysteries in which the soul was separated from the body in an initiatic sleep. “But Love was given when God became man in Christ Jesus. And the assurance that we can love beyond death, that by means of the powers won back for our souls a community of Love can be founded between God and man and all human beings among one another – the guarantee for that proceeds from the Mystery of Golgotha. In the Mystery of Golgotha the human soul has found what it had lost from the primal beginning of the Earth, in that its forces had become ever weaker and weaker. Three forces in three members of the soul: Will, Wisdom, Love! In this Love the soul experiences its relation to Christ”. 14

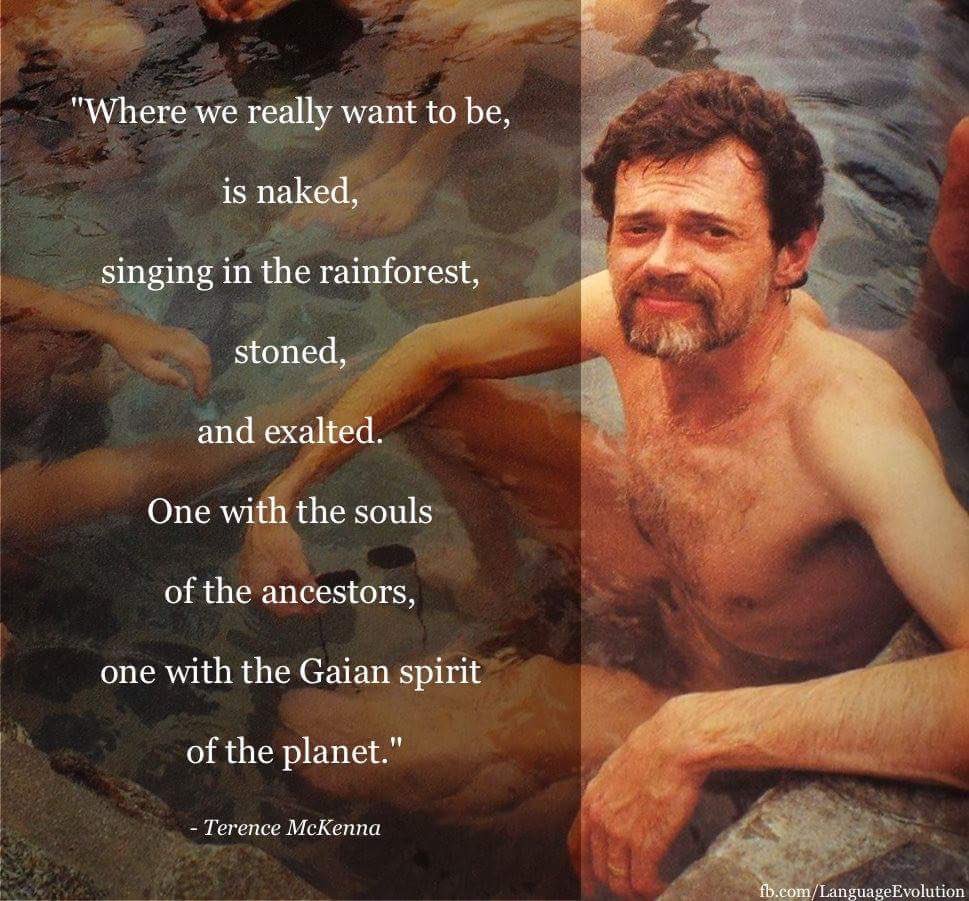

In the life experiences of so many musicians, artists, film stars and others one could witness how the young generation tried to find their way among these three soul forces, and in those who found their way to Love, even if they didn’t regard themselves as ‘church Christians’, one could feel something of Christian love in those people. On 25 June 1967, on the eve of the hippies’ ‘Summer of Love’ in California, in London The Beatles performed their song All You Need Is Love for the world’s first international satellite TV link broadcast which was seen by 400 million people in 14 countries around the world. The song began with a brass phrase from the Marsaillaise, the martial French national anthem. The first words of that anthem are: “Let’s go children, of the fatherland, the day of glory has come…” meaning ‘let’s go and kill the invading enemies of France’, but after that initial phrase from the brass, The Beatles morphed it immediately into a sung chorus of “Love, love, love”… .

The Beatles “All You Need Is Love” 25 June 1967

The turbulence of the 1960s threw up so many stark contrasts – between, for example, the collectivism of the ‘love-in’, the ‘be-in’, the ‘happening’ and the creative individualism of a John Lennon or a Jimi Hendrix, artists who very much went their own way. Hendrix (1942-1970), a unique genius of the new instrument, the massively amplified electric guitar, trod a path that passed from a flamboyant, libertarian, ‘luciferic’ or Dionysian individualism in early songs like “Stone Free”, “If 6 was 9” and “Are you Experienced?” to an affirmation of the collective values of his generation and his people in his last year of playing and recording (with songs such as “Message to Love”, “Angel”, “Power of Soul”, “Earth Blues”). In his last year, he was stretching out in various new creative directions, playing with a wider span of musicians, notably in the jazz field. It was tragic that his early death from apparent accidental barbiturate poisoning (too many sleeping pills) in 1970 at the age of only 27 cut short the great promise of his burgeoning career, which can be surmised from, for example, the great creativity shown in his Electric Ladyland double album (late 1968). Fans of his music and his musical peers were in awe of Hendrix’s dynamic live performances and his innovative creativity in the recording studio. He seemed to be on a different level altogether from all other rock musicians, although certainly, his generation did produce numerous extremely talented and creative musicians, many of whom shared the ideal of freedom and going beyond boundaries.

“Supermen”

On 13 May 1921 Steiner gave a lecture in which he said something he never repeated, most likely because, unfortunately, no-one ever asked him about it again: “…a time is beginning when beings who are not human are coming down to earth from cosmic regions beyond. These beings are not human but depend for the further development of their existence on coming to earth and on entering here into relationships with human beings.” This has been happening, he said, since the 1880s, and “it is thanks to the fact that beings from beyond the earth are bringing messages down into this earthly existence that it is possible at all to have a comprehensive spiritual science today.” He called these beings Übermenschen, which can be translated as “supermen” or beings who are “beyond human”. It is noteworthy that he does not call them ‘angels’ or ‘archangels’, but notes that the first to arrive were “beings dwelling in the sphere between moon and Mercury and associates others with (the presumably spiritual dimensions of) the planetary spheres of our solar system: Moon, Mercury, Sun, Jupiter, and Vulcan (a higher octave of Saturn). But, he said, humanity is ignoring them and shows no interest in having anything to do with them. This was of course truer in the 1920s than it is today, when countless Hollywood movies are concerned with aliens and UFOs, usually in an antipathetic sense. “It is this [ignoring of these beings] that will lead the earth into increasingly tragic conditions. For in the course of the next few centuries, more and more spirit beings will move among us whose language we ought to understand. We shall understand it only if we seek to comprehend what comes from them, namely, the contents of spiritual science. This is what they wish to bestow on us. They want us to act according to spiritual science; they want this spiritual science to be translated into social action and the conduct of earthly life… Upheaval upon upheaval will ensue, and earth existence will at length arrive at social chaos if these beings descended and human existence were to consist only of opposition against them… The beings I have spoken about will descend gradually to the earth. Vulcan beings, Vulcan supermen, Venus supermen, Mercury supermen, Sun supermen, and so on will unite themselves with earth existence. Yet, if human beings persist in their opposition to them, this earth existence will pass over into chaos in the course of the next few thousand years. People will indeed be capable of developing their intellect in an automatic way; it can develop even in the midst of barbaric conditions. The fullness of human potential, however, will not be included in this intellect and people will have no relationship to the beings who wish graciously to come down to them into earthly life.”

These beings are, therefore, apparently above human beings yet are not angels or archangels. If instead of welcoming them and their message of spiritual science, humanity continues with its intellectual way of thinking, it will create a plane of reality in the future that will cover the earth with what Steiner calls “spidery machine-animals”, “a horrible brood of beings… in between the mineral and plant kingdoms… beings resembling automatons, with an over-abundant intellect of great intensity, … a network or web of ghastly spiders possessing tremendous wisdom… In their outward movements they will imitate everything human beings have thought up with their shadowy intellect, which did not allow itself to be stimulated by what is to come through new Imagination and through spiritual science in general.” The movie trilogy The Matrix (1999-2003) showed a nightmarish picture of such a future dystopian world in which humans lived in an underground city called ZION, trying to shelter from the ‘machine-animals’ that dominated the ruined surface of the world. Meanwhile, human intellect had also created a computer simulation of the entire world into which human beings were drawn and made to live as programmes that did not challenge the machines’ control of the real world.

Steiner suggested in that lecture of May 1921 that such a ghastly future may well come about if humanity continues on its current intellectual course and does not turn towards the spirit, drawing new forces from the depths of human souls15, by paying attention to what the planetary ‘supermen’ wish to share with us. His picture, however, is not that of a Hollywood alien invasion by ‘greys’ or little green men in giant interstellar space ships. This is precisely a product of materialist, intellectual thinking. The beings Steiner had in mind evidently do not seek to interfere with our human freedom and do not impose themselves. It’s up to us to open ourselves to spiritual contact with them, for they are spiritual beings approaching us since the time, about 130 years ago, when the threshold between the spiritual and material worlds has been ‘thinning’ and humanity has been crossing the threshold unconsciously. Some human beings, especially in artistic fields, have evidently been more open to positive inspiration from such beings, while others, notably those in science and technology, have been inspired by beings at the threshold who are of a much less beneficent nature and which seek to push us into a dystopian future well before we are ready to cope. Acceleration is the leitmotif in this case which we need to be wary of, as well as the drives for ever more power and convenience. Once again, the 1960s offer many instructive examples of both positive and negative inspiration by beings at the threshold.

Conclusion

In anthroposophical terms, the 1960s began in an ahrimanic atmosphere of geopolitical fear and tension as well as one of a technological and Modernist optimism rooted in a materialist philosophy of life both in the capitalist and the communist blocs. The historic Vatican II Council was under way in Rome which would ‘reform’ various traditional aspects of the Roman Catholic Church, but the official Christianity of the churches was increasingly seen as failing throughout the West. However, by the middle of the decade, there had been a huge luciferic counterwave against the ahrimanic mood of the early 1960s, a great rebellious rejection by many young people of the conventional intellectual systems thinking of 20th century urban civilisation and a turning away from it back to the past and to non-western cultures, an inchoate seeking for a spiritual path or at least for personal freedom. This rebellion included empathy for and solidarity with oppressed peoples as well as the beginnings of the environmental movement and care for the Earth. In the midst of all this confusing miasma, in the year 1967, a theme broke through for a short time, which in its essence was Christian but was usually not identified as such at the time – the theme of Love, in the West at least, if not in the East, where the generational solidarity of the young Chinese Red Guards in the Cultural revolution (1966-76) was directed towards fanatical violence and hatred against older people and against traditional culture. That breakthrough of Love in the West was brief but it planted many seeds for the future, which have since grown vigorously.

What we can learn from our culture’s ‘failed initiation’ in the 1960s is to understand the evolution of consciousness and how things came to be how they are now, how they were in earlier times and how they need to move forward. Through a spiritual scientific understanding of cultural history, young westerners can begin to make more holistic sense of their culture’s complex story instead of the intellectual construct they are given at school and in the media. We can also learn that the unholy trinity of drugs, rock ‘n’ roll, and sexual license was and is but an unholy inversion of the eternal verities of the ‘holy trinity’ of the true, the beautiful and the good.

Endnotes

1. Karl Heyer, Kaspar Hauser und das Schicksal Mitteleuropas im 19. Jahrhundert, 4th ed. 1999, p.218.

2. Lecture of 14.12.1919, Collected Works, GA 194.

3. The term “Baby boomer” is something of a misnomer. They are the generation who were born during and in the aftermath of the Second World War, with Neptune in Libra, 1942-1956.

4. E.g. Martin Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams – The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond (1985).

5. See Lee & Shlain pp.157-160.

6. See Lee & Shlain , p. 163.

7. From an anthroposophical perspective, one can easily discern the whole gamut from ‘luciferic’ influences (in dreamy neo-folk and neo-tribal music) to ‘ahrimanic’ influences (in hard rock and the first manifestations of occultic, even satanic, heavy metal and proto-punk) in these years – and all things in between, as the searching human soul tried to find its way between the two compulsive poles of the luciferic and the ahrimanic. Indeed, one could say that between 1963 and 1973 almost all the subsequent musical developments of the next 40 years and more can be found in seed form in those 10 years.

8. Epic poems published in 1761-65 purported to be by the ancient bard Ossian but were actually by the Scottish poet James Macpherson (1736-1796).

9. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terence_McKenna

10. See n. 9.

11. See R. Steiner, Anthroposophy – An Introduction (Rudolf Steiner Press, 1983).

12. See Lee & Schlain, p. 89.

13. See R. Steiner, The East In the Light of the West (1922).

14. R. Steiner, Christ and the Human Soul, 12 July 1914. GA 155.

15. R. Steiner, lecture of 14.12.1919, GA 194.